The Colour of Lucy’s Hair: The “Nightmare” of Female Sexuality in Dracula

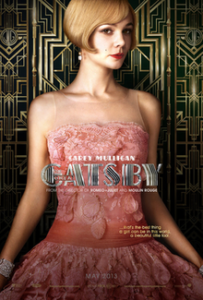

Bram Stoker is a notoriously careless writer, capable in Dracula (1897) of locating Shooter’s Hill in North London. Unless we bend over backwards to claim that he was actually intent on creating an uncanny version of that city, it does seem a genuine error and a surprising one given that Stoker lived half his life span in the capital. He was probably referring to Shoot Up Hill which is in closer proximity to Hampstead. Similarly, Van Helsing in that same novel twice slips inexplicably from his native Dutch to German, exclaiming “mein Gott” rather than “mijn God!”. For this reason, the reader might overlook the fact that while Seward describes Van Helsing as combing Lucy’s hair into “sunny ripples” just prior to death in chapter XII, she is described by the same narrator posthumously in the graveyard in chapter XVI as “dark-haired”. The film still below opts to retain the original hair colour!

Bram Stoker is a notoriously careless writer, capable in Dracula (1897) of locating Shooter’s Hill in North London. Unless we bend over backwards to claim that he was actually intent on creating an uncanny version of that city, it does seem a genuine error and a surprising one given that Stoker lived half his life span in the capital. He was probably referring to Shoot Up Hill which is in closer proximity to Hampstead. Similarly, Van Helsing in that same novel twice slips inexplicably from his native Dutch to German, exclaiming “mein Gott” rather than “mijn God!”. For this reason, the reader might overlook the fact that while Seward describes Van Helsing as combing Lucy’s hair into “sunny ripples” just prior to death in chapter XII, she is described by the same narrator posthumously in the graveyard in chapter XVI as “dark-haired”. The film still below opts to retain the original hair colour!

Lucy in this latter sequence clutches to her breast in a parody of motherhood a “fair-haired child” and we might reason that Stoker has been betrayed into dyeing, as it were, one of his character’s hair, in order to engineer a simple visual contrast at this point of the narrative alone between the innocent quarry and the pitiless, posthumous predator.

There might, of course, be another explanation in which the two hair colours attributed to Lucy function symbolically to reflect two different facets to her personality: one of which Victorian culture prizes and the other by which it is troubled.

Let us return to Lucy’s death bed and specifically to Van Helsing’s attempts to beautify Lucy prior to her fiancé Arthur bidding farewell to his dying bride. Seward praises Van Helsing for displaying his “usual forethought” but the reader may actually feel distinctly queasy about the latter’s actions. They are reminiscent of a mortician, the aim being to tidy Lucy up before her grieving fiancé enters the, soon to be, “chapelle ardante”. Seward describes how he made “everything look as pleasing as possible”. Van Helsing is intent on creating a palatable version of Lucy, one that suits Victorian conceptions of femininity.

Let us return to Lucy’s death bed and specifically to Van Helsing’s attempts to beautify Lucy prior to her fiancé Arthur bidding farewell to his dying bride. Seward praises Van Helsing for displaying his “usual forethought” but the reader may actually feel distinctly queasy about the latter’s actions. They are reminiscent of a mortician, the aim being to tidy Lucy up before her grieving fiancé enters the, soon to be, “chapelle ardante”. Seward describes how he made “everything look as pleasing as possible”. Van Helsing is intent on creating a palatable version of Lucy, one that suits Victorian conceptions of femininity.

What Van Helsing does in this sequence is repeated in more radical and disturbing form in Lucy’s tomb. The “Crew of Light” (as Christopher Craft problematically describes them) gather to conduct a peculiar ceremony on what would have been very close to Lucy and Arthur’s wedding day. Again Stoker’s carelessness may be to the fore here because if the dating was intentional, the facts actually are that

Arthur and Lucy were to be married on the 28th and the ceremony in the tomb takes place a day later. Nonetheless while Van Helsing reads from a “missal”, it is fiancé Arthur who puts a stake through Lucy’s heart. The corpse initially writhes as though in the throes of orgasm but in a short time becomes passive, immobile, in a word, dead: the Victorian ideal of womanhood, perhaps? It is at this point that Van Helsing, now playing the part of a clergyman as opposed to a mortician, permits Arthur to “kiss her dead lips”. Having noted the apparent carelessness of Stoker’s writing style, I’d like to acknowledge his capacity on occasion to write with real deliberation. Van Helsing’s words recall a significant variant on them when Jonathan Harker at Castle Dracula, encountering the ‘Vampire Brides’ admits his desire to “kiss those red lips” in chapter III. Jonathan’s desire is a forbidden one and not just because he is affianced to Mina Murray. He is powerfully attracted to the overt sexuality of these women and like Van Helsing later in the novel, profoundly troubled by this very attraction. The latter’s desire for the women he needs to destroy leads to a delay but it is surely not the cessation of desire that enables him to carry out the triple staking, so much as a need to punish these women for the desire they have generated in him. Arthur is

similarly drawn to Lucy in her more seductive form. As Lucy slips into “a sort of sleep-waking, vague, unconscious” state, she speaks seductively to Arthur and the latter responds. Only Van Helsing’s intervention prevents the interaction between a responsive male and equally responsive female. Van Helsing’s actions uncannily echo Dracula’s, though most readers, I take it, tend to assume that because their motivations differ considerably, Van Helsing can be exonerated.

That sequence in the Lucy’s tomb does not seem to have invited much of a contemporary response. The novel was seen as an exciting adventure yarn and its psycho-sexual content entirely unacknowledged. It was H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau, published a year before Stoker’s novel, that drew both the fire and ire of its initial reviewers. Dracula seems to have been categorised alongside Ryder Haggard’s She (1887) as wholesome adventure! More recent critics have been very troubled by the sequence and Carol Senf has described it as “a combined group rape”. It seems to me to be the absolute opposite of this. The strange ceremony in Highgate cemetery is actually one aimed at re-inscribing the very monogamy that Lucy had challenged in her letter to Mina in chapter V: “why can’t they let a girl marry three men, or as many men as want her?” Lucy’s voraciousness is reflected in the novel by the fact that by the end of the life four men have given her one of their bodily fluids. The sexualisation of transfusion in the novel is reflected in the fact that the fiancé, Arthur is kept in ignorance of the fact that he was not the only donor. It would, according to Van Helsing “enjealous him”. Indeed, in taking less blood from Seward than Lucy’s fiancé Van Helsing strives absurdly to regulate the polyamory transfusion has unleashed. The ceremony in the tomb is intended to eradicate Lucy’s polyamorous tendencies and it is notable that Van Helsing hands Arthur the key to the tomb at the end of the sequence. One lock, one key: “the sexual implications” (as Elaine Showalter says of the whole sequence) are embarrassingly clear” here. I echo Showalter’s words in specific reference to Van Helsing’s gesture here – which has generated little critical comment.

That sequence in the Lucy’s tomb does not seem to have invited much of a contemporary response. The novel was seen as an exciting adventure yarn and its psycho-sexual content entirely unacknowledged. It was H.G. Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau, published a year before Stoker’s novel, that drew both the fire and ire of its initial reviewers. Dracula seems to have been categorised alongside Ryder Haggard’s She (1887) as wholesome adventure! More recent critics have been very troubled by the sequence and Carol Senf has described it as “a combined group rape”. It seems to me to be the absolute opposite of this. The strange ceremony in Highgate cemetery is actually one aimed at re-inscribing the very monogamy that Lucy had challenged in her letter to Mina in chapter V: “why can’t they let a girl marry three men, or as many men as want her?” Lucy’s voraciousness is reflected in the novel by the fact that by the end of the life four men have given her one of their bodily fluids. The sexualisation of transfusion in the novel is reflected in the fact that the fiancé, Arthur is kept in ignorance of the fact that he was not the only donor. It would, according to Van Helsing “enjealous him”. Indeed, in taking less blood from Seward than Lucy’s fiancé Van Helsing strives absurdly to regulate the polyamory transfusion has unleashed. The ceremony in the tomb is intended to eradicate Lucy’s polyamorous tendencies and it is notable that Van Helsing hands Arthur the key to the tomb at the end of the sequence. One lock, one key: “the sexual implications” (as Elaine Showalter says of the whole sequence) are embarrassingly clear” here. I echo Showalter’s words in specific reference to Van Helsing’s gesture here – which has generated little critical comment.

Lucy’s two facets reflected by the two different hair colours attributed to her are related in the novel to the conscious and the unconscious. She is “voluptuous” only in the latter state. Seward, one of Lucy’s suitors, comments that the seductive tone of voice she adopts when unconscious is unfamiliar (literally in Freudian terms unheimlich) to him but it is also implied that it is similarly foreign to her fiancé. Mina commenting on her privileged position in being Lucy’s bedfellow, speaks of how much more intense Arthur’s feelings might be had

he not just encountered her “in the drawing room”. It is the yawning gap between ‘drawing room’ and ‘bedroom’, between courtship and consummation, in Victorian society, one might argue, that accounts for the way the men conceive of respectable woman in such a neutered way.

It is one of the great rewards of reading Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber (1979) that it sends the reader back to Dracula with a new set of perspectives, to look anew at Stoker’s fin de siècle novel through Carter’s post-Modern spectacles. In particular, and appropriately I want to end this article by looking briefly at Carter’s vampire story, ‘The Lady of the House of Love’. I want to intercept it at a point of apparent digression from the action, when the Edwardian cyclist the narrative tells us, recalls his colonel offering him the chance of visiting a Parisian brothel where the speciality of the house was the option for intercourse with a girl in a coffin, playing dead. Carter’s story is set a matter of 17 years after the publication date of Stoker’s novel (though published 82 years later) and there is surely a similarity in the attitudes of these Victorian and Edwardian gentlemen. The colonel in the anecdote we can surmise needs the prostitute to play out a role at absolute variance to her profession. The sexualised woman is required to play a part that denies the reality of her promiscuity, of who she really is. It is, I contend, this

woman rather than the Countess who is the titular figure of Carter’s story: she is ‘the lady of the house of love’. If so, the ostensible digression becomes absolutely central to our understanding of Carter’s story and, I propose, Stoker’s novel. Though the Edwardian cyclist foregoes the colonel’s immodest proposal, his desire at the end of the story to get the eldritch aristocrat “to a dentist to put her teeth into better shape (and to seek out a)…competent manicurist (to) deal with her claws” is notable. His ambitions on her behalf (in fact his) underline Victorian/Edwardian male anxieties about overtly sexual women. Carter uses free and indirect style in having the young man propose that “we shall turn her into the lovely girl she is” but if she is what he claims her to be, then his desire to transform her into something else makes no sense! His use of the first person plural is also notable for it as though he speaks on behalf of half the human race: all men should wish for this ‘make-over’. His thought process concludes with the confident claim that,” I shall cure her of all these nightmares.” You may be reminded of the description of the ‘undead’ Lucy in her coffin: Seward says of the wraith, “she seemed like a nightmare of Lucy” for while the Edwardian cyclist speaks of the Vampiress’ “nightmares”, it is surely she who in her voracious form is his and his culture’s nightmare. His aspirations to beautify his uncanny

hostess recall my starting point: the beautifying of Lucy by Van Helsing.

Leslie Fiedler in his classic work Love and Death in the American Novel (1960) uncannily makes the same claim about Daisy Buchanan in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby (1925). He notes that she is identified both as blonde and as brunette and that these hair colours correspond to her status as respectively a “fairy” in Gatsby’s life and his “dark destroyer”. The most recent film version of The Great Gatsby depicts Daisy as blonde whereas in the first film version (1926) Daisy was played by the brunette Lois Wilson. Either hair colour would have worked equally effectively in this black and white version.

I am queasy about identifying either Daisy Buchanan or Lucy Westenra as ‘dark destroyers’ but in both cases the identification of female protagonists with two hair colours certainly reflect their capacity to destroy the only partial conception the male protagonists have of them.

They only know the half of it.